How to create an environment of child development that gives all children and youth wings?

18. mars 2016 / Bjorn Hauger bjorn

SmART Upbringing – a magical development project in Re County.

Bjørn Hauger, Elisabeth S. Paulsen and Vidar Bugge-Hansen

In this sketch we wish to describe an action research project connection with a development project for the improvement of conditions of upbringing for children and youth in Re County, Vestfold. This development project has been named Smart Upbringing and is described as “one of the broadest and most comprehensive projects ever conducted for strengthening the environment of upbringing for children and youth in Re County” (Grejs, 2013).

The development of this project can be understood in the light of the emergence of a new discourse in the public sector about how processes of change can occur there. The conventional understanding (Kuvaas and Dysvik, 2011) is characterized by goal-rational and linear thinking. Within such a paradigm, goals are understood as “independent” of the people doing the work to achieve them. One can further surmise here that planning and completion are separate processes. The initiative for change that has its origin in such a discourse often comes “from the top” of the organization and the strategy is dominated by a mind set in which one is to “get things done” (Kemmis, McTaggart and Nixon, 2014) and in which one is more concerned with changing others than working together (Higgs, 2011).

In recent years, an increased consciousness has gradually developed of alternative approaches to organizational development and processes of social change. This is articulated in strategies based on a more humanistic view of people and collaborative approaches to work with processes of change (Kuvaas and Dysvik, 2011). In Re County there has long been testing of different forms of collaborative strategies in work with organizational development. In 2002-2003, for example, all the preschools employed Appreciative Inquiry (AI) as an action research strategy in connection with quality development; all the employees were involved. The plans for what was to be improved and how these improvements should occur were made collaboratively. In this work, several different ethnographic methods were also used in order to access children’s voices in the work of development (Hauger, 2003). Those who participated in the training program also received training in how they could create new “communicative spaces” in the preschool characterized by dialogue that could enable people to bloom (Reason and Bradbury, 2006).

Background.

In 2005, one of the schools in Re County decided to employ Appreciative Inquiry as an approach to work with the creation of a new vision for the school. A short time afterwards, the County decided that all school leaders should be trained in work with management and organizational development based on the same perspective.

It is in the wake of this training and development work that Smart upbringing arises as a new generative idea about how one can combine and change preventive programs for at-risk children and youth with strategies for releasing the individual child’s – and organization’s – potential (Appreciative Inquiry).

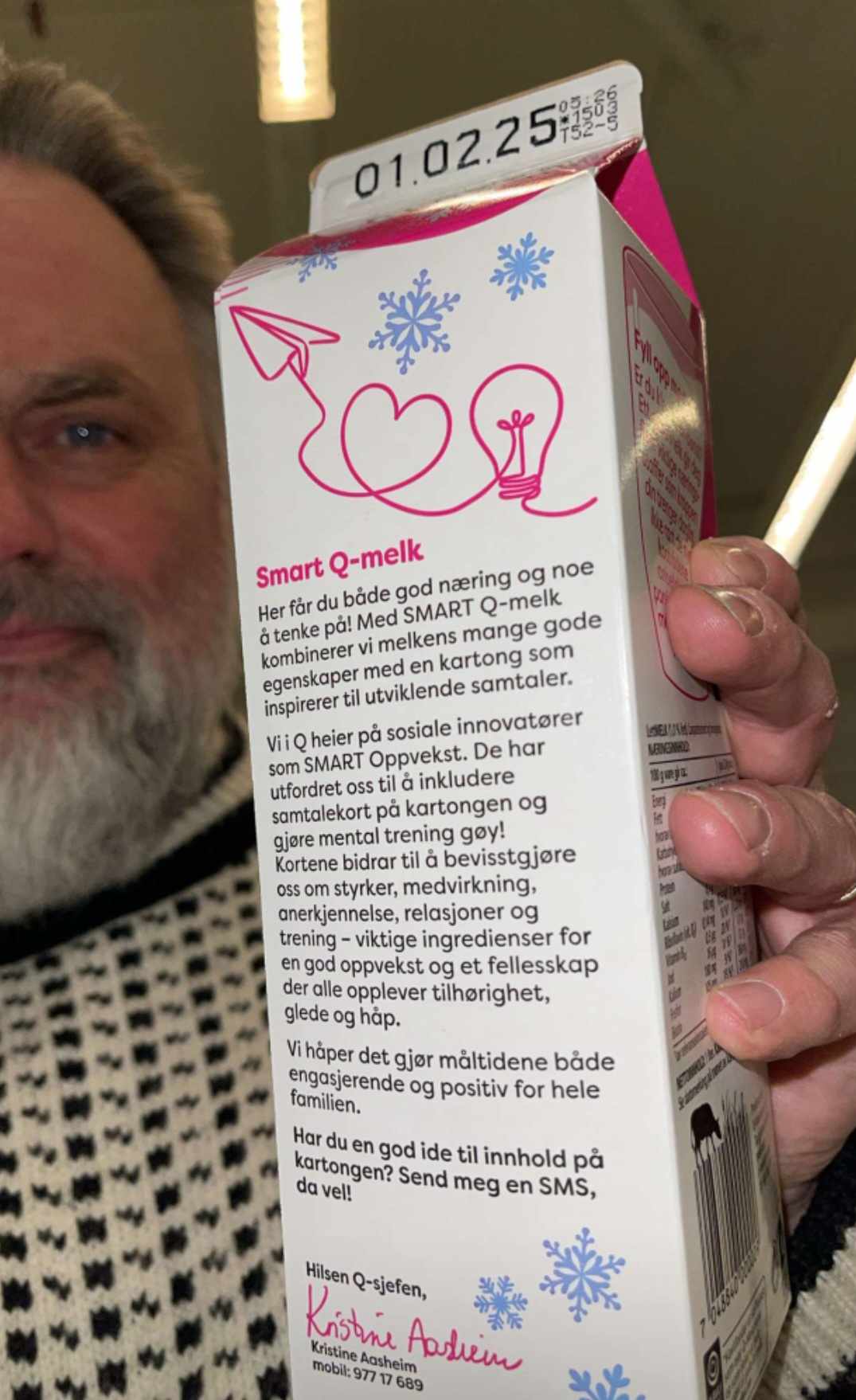

Originally, “Smart upbringing” was viewed as a pedagogical implementation; a way of working preventatively and inclusively in relation to at-risk children (Bugge-Hansen, et al. 2013) in the individual school and preschool, and it became a unified project involving preschools, schools, Pedagogical-psychological services, the health service, parents, children and youth’s leisure arenas. The project is further described as a strategic intervention to involve “all, from children to politicians” in the work of Development.

Viewed from a social constructionist perspective, this developmental work appears particularly exciting because of the ideas that underpin it: One can imagine that if one is to do anything with the patterns of actions that lead to many children and youth being discounted, not seen as important, clever or valuable, we must change the way we understands, talks about and creates meaning in one’s our practice. Through the project, “Smart upbringing”, the County has set the goal of changing a culture dominated by a defensive and problem oriented mind set, to an offensive strengths-based one. Through changing the dialogue between professionals, children and their parents, through posing new kinds of questions, through introducing a new professional language (among other things, about strengths [1]), and planning a new choreography of conversations, we hope to be able to change practice in a more radical way than if we continues to work with change interventions based on traditional modes of understanding. Instead of placing weight on what it is that leads to so many children and youth being unable to cope with their school life, we are focusing on the children’s individual strengths and possibility to create new ways of shaping the future. This give all children and youth the opportunity to reach their potential in a better way.

In the course of the years the project has existed, hundreds of employees, children, youth and their parents have been involved in the developmental work. The discourse that characterizes these conversations is changing. New collaborative arenas characterized by more hopeful dialogues are being established. The voices of children, youth and their parents are promoted in a completely new way and with a new power than before. Enthusiasm has been created among professionals, managers and politicians that has attracted attention beyond the County’s borders.

New discource

In our society, discourse connected with learning and development work is associated with a problem perspective. In order for something to be defined as a problem, there must exist an impression about what the opposite of the problem is, that is, what it means when something is good. When students are restless during a lesson and this is perceived as a problem it becomes a problem when you expected good behavior is that the children are quiet.

In many organizations, a great deal of time is used in the identification of problems, and what should be done to solve them, or create improvements. When organizations begin to explore their weaknesses and flaws, the result can be that the divisions between people increase, and conversations will be in the direction of interventions that have to do with control, correction and punishment.

AI operates with a different discourse. People and organizations are regarded as having possibilities for functioning in many different ways. Exploration of that which is life-giving and the expectation that all people have uniquely positive qualities and strengths is to simultaneously promote these aspects and contribute to the development of the capacity for creativity and innovation (Barrett and Fry, 2008). AI can therefore be understood as an artifact, a way of regarding the world. In the beginning of an AI process, employees and managers train themselves to see one another and one another’s contributions to the organization through “positive lenses” (Goldon-Biddle and Dutton, 2012) through use of unconditionally positive questions.

Project SmART upbringing is a large-scale complex form of development work that is conducted at various levels in the County, and across all the arenas of work with children and youth in the County. We wrote earlier about how the development of the design of an action research project should occur in collaboration with the participants of the project. We wish also to suggest that the general theme of this action research project concerns exploration of the generative potential of Smart upbringing and that it can be useful to begin the first action-reflection cycle with an acknowledging exploration of the kinds of social innovations already exist, what has made this possible, what the life-giving factors of the process are, and so forth.

Based on such an investigation, the next task can be spending time with the participants in (re)formulating a normative vision for the project, in order to look for new possibilities for these norms to have expression in practical actions. We are particularly interested in learning more about what is required for the new norms to be put into practical interaction with children and youth. In this context, we would be interested in looking for new opportunities for involving several children and youth as co-researchers and creators of the new practice. This has already begun in the project. The girls have had training in leading girl groups, and students attending 7th grade in one of the elementary schools have lead processes in which all the children in the class have researched one another’s strengths. We have experience with involvement of children as co-researchers in the development of the class environment in an elementary school (Hauger and Karlse, 2005), and work with the application of ethnographic methods in order to access children’s voices and experiences in a quality development project in the Preschools.

However: as we have written previously, these are only examples of ways of involving children and youth as co-researchers. Whether or not this is useful and the way it should occur must be discussed in the project. We wish merely to add here that this way of working is in accordance with the central values and principles of action research. It concerns among other things the involvement of many participants in the research in order to create a more inspiring future for oneself and others.

[1] The County has, among other things, developed a tool for children from the age of 5 years up (in preschool and school) used to teach them to research positive experiences between adults and children, and between children in different everyday situations. The tool consists of a book with an array of stories about moral dilemmas in the everyday lives of children and a vocabulary (printed on cards) that children can use to describe good qualities (strengths) that are expressed in the valued actions depicted in the stories (Våge and Bugge-Hanse, 2012; Våge and Bugge-Hansen, 2013).