Hvordan jobbe med A – anerkjennelse i klasserommet

26. mars 2016 / Eira Susanne Iversen eiraiversen

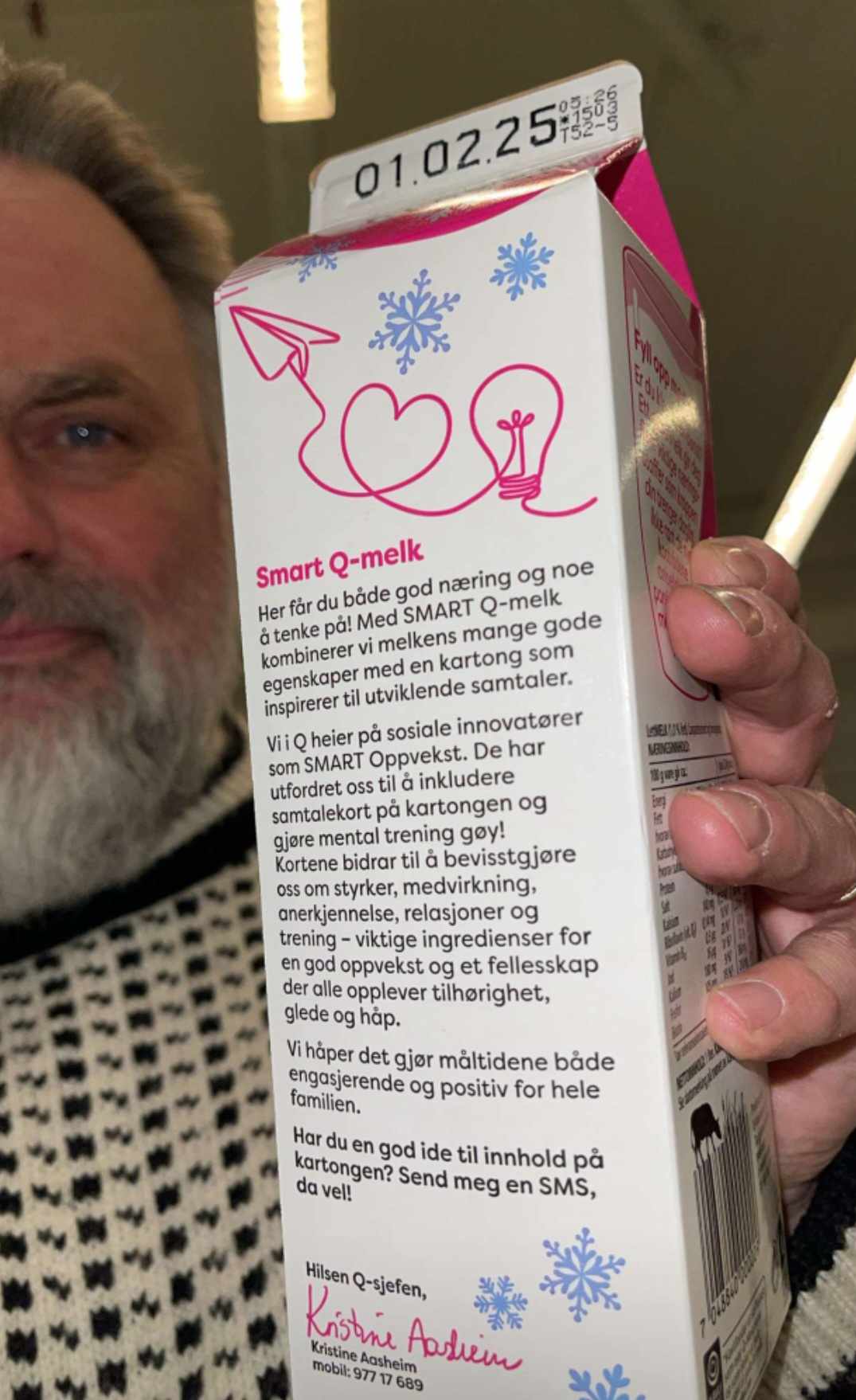

Jeg jobber som kontaktlærer på 4.trinn i år samtidig som jeg har en 30% stilling i SMART oppvekst i Re kommune. SMART bokstavene står for de verdiene vi synes definerer hva smart oppvekst er: S – styrkefokus, M – medvirkning, A – anerkjennelse, R – relasjoner, T – trening. Prosjektleder Vidar Bugge-Hansen har skrevet mer om dette i sin blogg: Smart oppvekst – som kompass. Slik forklarer han A’en i SMART:

A – anerkjennelse. ALLE må oppleve å bli sett på med positive øyne og bli fortalt med ord og kroppsspråk at man er verdifull. Dette er mikroferdigheter som kan skape oppadgående eller nedadgående spiraler i relasjonen og i den andres liv. Uenighet og ulik forståelse er kilde til framgang og refleksjon. Ved å prøve å være gjest i den andres tanker og prøve å forstå hvordan verden ser ut herfra vil man også kunne oppnå anerkjennelse og gode relasjoner også i slike situasjoner.

For meg er dette slik jeg ønsker å møte alle, med anerkjennelse og forståelse av deres perspektiv. Hvis jeg skal være helt ærlig har jeg en ganske så positivt syn på mennesket. Det er ikke alltid like lett å ha når man ser hva som skjer i verden, men jeg velger likevel å tro på at alle gjør så godt man kan. Det er bare det at noen ganger så blir ikke utfallet av slik man handlet så godt. Men jeg velger å tro at det ikke finnes onde barn. Det finnes barn som gjør ting som er uheldig for de rundt, som ikke tenker konsekvenser eller hva andre kan tro om deres handlinger. Derfor prøver jeg å lære dette til barna jeg har rundt meg. La meg komme med et eksempel;

Det er norsktime og jeg har gitt beskjed om at alle elevene skal hente norskbøkene sine i skuffen sin. I mitt klasserom, som i alle andres regner jeg med, blir det å komme først til skuffen en konkurranse. Skuffesksjonen som elevene har bøker i er ekstremt lite effektiv, og elevene blir stående i kø å vente til den foran er ferdig. Dette er et fødested for konflikter og denne dagen kom to gutter tilbake til klasserommet gråtende. Den ene hadde slått den andre i bakhodet fikk jeg høre. Jeg kunne sagt «fy deg for å slå» og «si unskyld» og fortsatt med undervisningen. Men jeg føler det blir liten læring av disse ordene og som ikke løser noe som helst. Istedet pleier jeg å forske i hva som hendte. Jeg var aleine som lærer denne timen og hadde ikke mulighet for å ta guttene ut. Dessuten synes jeg det vil frarøve de andre elevene, som har sett hele situasjonen, mye læring. Det er jo altid slik at elever holder med hverandre utifra hvordan de tror situasjonen oppsto. Jeg går inn i hvert perspektiv og lar de fortelle.

-Fortell meg hva som skjedde, Henrik?

-Roar slo meg, sier han.

-Ja, sier jeg , det var ikke noe godt og det kan jeg godt forstå.

-Fortell fra begynnelsen, hva skjedde? Gutten forteller at han sto i kø og følte han foran tok så lang tid. Han ba han bli ferdig fort, og da svarte gutten foran med å slenge en bok i hode på han.

-Hvordan var det å vente i kø?, spør jeg.

-Det var kjedelig, jeg tenkte på at jeg ble sein til timen og jeg følte han brukte lenger tid enn nødvendig. Jeg kjente stresset i magen, forteller han videre. Jeg spør alltid hvor følelsen sitter og ber de beskrive den slik at de utvikler begreper på følelsene sine og kan kjenne de igjen.

-Det boblet i magen og hjertet dunket, fortalte han.

Så det er kø og de i køen er utålmodige, hvordan opplever du det, Roar? spør jeg gutten som hadde stått først i køen.

-De bak meg presset meg mot skuffen så jeg ikke klarte å åpne den. Jeg ble sint da de ikke hørte på meg da jeg sa jeg ikke klarte å åpne skuffen. Sinnet boblet i magen og jeg ble varm i ansiktet. Så da jeg fikk opp boken kastet jeg den bakover.

Når begge parter har forklart hvordan de følte situsajonen og forstår hvorfor de har oppført seg slik de gjorde er det skjeldent behov for en unnskyldning. Ingen av de ønsket at det skulle bli som det ble. Det var ingen ond handling som ble utført. Meningen de hadde puttet på situasjonen er borte og saken er løst. På denne måten blir begge parters følelser og opplevelse av situasjonen anerkjent. Når vi forstår hvorfor forsvinner behovet for en unnskyldning og. Det blir mer korekt å si; «Det var ikke slik jeg mente det skulle bli».

Det er mange måter å jobbe med anerkjennelse med barn. Her er noen eksempler;

Anerkjennelse i klasserommet:

- Moralske dilemma situasjoner – I SMART oppvekst bøkene finnes det flere moralske dilemmaer man kan diskutere i klasserommet eller i barnehagen. Her er det viktig at vi som voksne ikke kommer med «riktige» løsninger, men holder oss nøytrale. Det er elevenes svar som skal spilles mot hverandre. Som lærer må jeg da si ting som speiler det de sier, oppsummerer det de sier og svare med nøytral stemme. Men samtidig anerkjenne alles svar slik at de føler at det de sier er viktig.

- Snakke om hvordan det føles å ikke bli hørt på når man skal fortelle noe. Hvordan ønsker du andre skal opptre? Hvordan føltes det da?

- Lage plakat i klasserommet som handler om hvordan vi skal være med hverandre; Lytte til hverandre, se hverandre inn i øynene, nikke, smile, stille spørsmål og avslappet foroverlent kropp.

- Konflikthåndtering: Undersøke andres perspektiv. Hva skjedde? Det forstår jeg du følte. Det ville jeg også følt hvis jeg hadde oppled det samme. Hvordan kunne du ønske det skjedde?

- Sosialkonstruksjonisme perspektivet: Alle opplever en situasjon ulikt. Det er sammen vi kan finne ut hva som skjedde. Ved å forstå hvordan vi oppleved det som skjedde og hvilke merkelapper vi har puttet på situasjonen. Det er er ofte det ungen tror om situasjonen som gjør at det er vondt for dem. Det er ikke en sannhet, men flere sannheter.

- Ta alle elevene i hånden når de kommer inn i klasserommet imens du ser de i øynene.

- Hilse på morgen, øyekontakt og hei.

- Si hei. Det er mer virkningsfult når man bruker navnene til hverandre. Hei Eira, Hei Vidar osv.

- Hei- prosjekt på skolen: Alle elevene gikk med navnelapper en uke slik at vi kunne si «Hei …..» til dem.

- Lytte til det de har å fortelle og vise at man synes det er fint å høre. Følge opp med spørsmål.

- Anerkjenne styrkene de har.

Jeg tenker at ofte kan det virke som om barna trenger hjelp eller råd. Men så er det anerkjennelse de trenger for å komme seg ut av følelsen de opplever, eller/og for å føle seg sett og forstått. Dette er ikke noe som bare er for barn, men for alle mennesker i alle aldre.

Jeg tenker at ofte kan det virke som om barna trenger hjelp eller råd. Men så er det anerkjennelse de trenger for å komme seg ut av følelsen de opplever, eller/og for å føle seg sett og forstått. Dette er ikke noe som bare er for barn, men for alle mennesker i alle aldre.

Her er flere blogger om de andre bokstavene i SMART: S-styrkefokus i klasserommet og M-medvirkning i klasserommet.

Jeg er sikker på at du har mange andre måter å anerkjenne barna på. Del med oss på vår facebookgruppe og lik oss på vår side og få med deg nyheter fra oss.

Lykke til!

Eira Susanne Iversen

Lærer, forfatter og SMART konsulent